By Nathan Morley

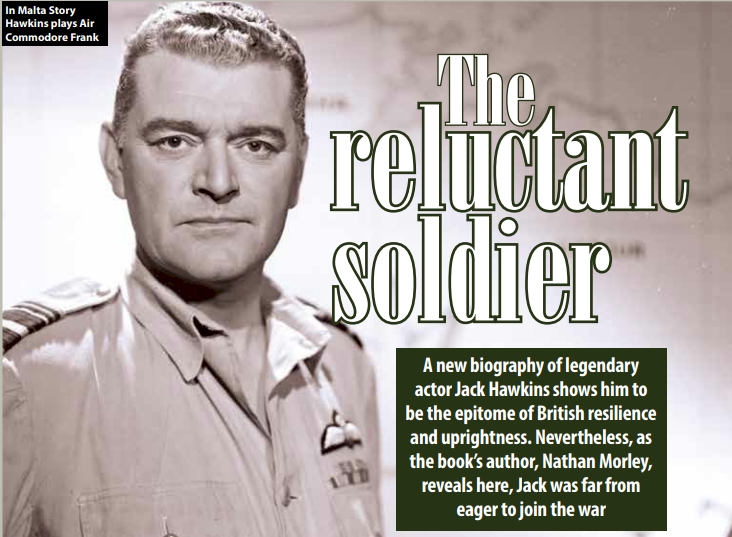

Britain’s most famous stiff‐upper‐lip hero – and star of The Cruel Sea, Malta Story, Bridge on the River Kwai and Angels One Five – was a rotten soldier during the Second World War.

However, that’s not to say he didn’t do his bit, because he did. It was just not the kind of war we imagine the solid, sturdy, responsible Jack Hawkins fighting.

Whilst researching my new biography of Hawkins, the late Sir Michael Parkinson remarked to me, nobody could mimic Jack’s unique sense of restraint: “He was a formidable presence in the British film industry and one of those trustworthy stars who an audience loved because he made them believe that everyone was as decent and brave as Jack Hawkins.”

It is true that in a restless world, his rugged on-screen persona made him appear as steady as a rock, the sort of man you know you could always rely on, especially in wartime.

However, in reality, during 1940, as Britain stood alone, Jack was one of the busiest actors in London, and enjoying all of the trappings of fame and wealth. He absolutely hated the thought of joining up, and stalled for as long as possible before appearing at the recruiting office.

Ultimately, though, after the terrible events in Dunkirk, a sense of patriotic duty saw him ‘idling around the back door of the War Office’ before his colleague, Andrew Cruickshank, – who later found fame playing Dr Cameron in Dr. Finlay’s Casebook – volunteered to join the Royal Welch Fusiliers.

“At the theatre that night I told Jack Hawkins and Andre Morell what I’d done,” Cruickshank recounted. “They cursed me—and volunteered soon after.”

In a recent interview, Cruickshank’s daughter, Harriet, told me her father joined the Fusiliers because her mother, Curigwen Lewis, was Welsh. “He always told us children that Jack Hawkins joined the same regiment although as you can see, they didn’t join up at the same time. They did remain friends of course.”

So, after wangling his way into khaki, Jack joined many thespian brothers-in-arms, including Alec Guinness, who received a commission in the Navy, Ralph Richardson who joined the Fleet Air Arm, and David Niven, who abandoned Hollywood to march with the Rifle Brigade.

What first annoyed Jack was the basic training as an unpaid lance-corporal. Day after day, he traipsed around the parade ground until his boots produced blisters. However, after five months, he was ‘picked out as officer material’ and sent to the Training Corps at Pwllheli.

This, however, turned out to be an even more miserable experience.

Confronted with abysmal conditions, his days were made up of an exhausting routine of digging trenches and shooting wildly at cardboard targets. “This was the way things were done,” he gloomily appraised, “this was the world whose strict rules of discipline I adopted. But I began to regret not remaining a private soldier.”

Eventually, he was issued a second lieutenant’s uniform, complete with prince of Wales plumes, coronet, and circlet insignia of the Royal Welch.

Thankfully, life wasn’t all spit and polish. During leave breaks, he patronized the Marlborough Arms, the 400 Club, and the Savoy. La Popote, hidden in the basement of the Ritz, became his favourite supper spot during the buzz-bomb raids and blackouts.

And he was allowed to continue acting.

During the summer of 1941, he appeared in the War Office production of Next of Kin, a propaganda film set in Nazi occupied France warning audiences of ‘careless talk’ and loose lips, starring Mervyn Johns and Ronald Adam. Though Jack’s part was small (billed as ‘2nd Lt. Jack Hawkins’) he oozed authority playing a British officer, giving an early display of the solid-sturdy temperament for which he later became famous.

For a while, the film was banned from public exhibition on the orders of Winston Churchill who thought it revealed to the enemy how the British could inflict damage on them. Strangely, though, the press charged it was made to ‘frighten the masses into keeping their mouths shut’.

After Next of Kin, Jack’s life in the military fell into place. As the German’s approached Moscow, and the fighting in North Africa raged on, his days were spent helping women ATS recruits in Cheltenham learning to repair shortwave radios.

Though an extremely cushy number, the posting didn’t last long.

After being instructed to collect his fighting kit, the thirty-three-year-old lieutenant was inoculated for yellow fever, cholera, smallpox, and typhoid, before joining the British 2nd Division on a long voyage to India.

On arrival in this lively theatre of war, he led a Bren gun platoon deep inside the Indian jungle—a shadowy terrain, bursting with venomous snakes, spiders, and mosquitoes.

The most dreaded snake was the Russell viper. When it struck, there was only one thing to do. Get a sharp razor blade and hack out the flesh round the bite. “It was pure hell,” Jack reminisced.

In the face of such horror, far from suggesting grace under pressure, he failed to take it all in good humour and could often be heard loudly cursing and grousing from his rain-soaked foxhole, as his enthusiasm for army life boiled away.

Worse still, as his temper rose, he noisily declared his heartfelt ambition to ‘stay alive’.

You might think such behaviour would have landed him in jankers or at least kicked-back into the ranks.

However, the army works in mysterious ways, and he was plucked from the jungle and given ‘light duties’ at the Poona Divisional Battle School, an oasis of calm in India, where his job was to narrate demonstrations of combat techniques over a loudhailer for visiting top brass.

At the intervals, he propped up the NAAFI bar, and – to spice things up – helped produce the occasional concert show. Major Donald Neville-Willing, a hotshot impresario, never forgot catching an early performance.

“One turn was listed as a Spanish dance and song act,” he remembered. “On to the stage came prancing a magnificent figure of a woman clacking castanets and casting amorous looks at the boys in the audience. I don’t know if anybody fell for this apparition. There was certainly no excuse when the ‘senorita’ opened her mouth to sing. Out came the manly baritone of Jack Hawkins.”

These were happy times. A surviving snap shows Jack wearing a khaki tunic with a cigarette dangling from his lips, jauntily holding what looks like a script.

Before long, he was seconded to ENSA, the entertainments branch, to oversee a vast portfolio of actors, comics, and musicians. He proved to be a superb organizer and became the colonel in charge.

One journalist, intrigued by his enthusiasm, noted how Jack pioneered the concept that soldiers would like “something other than a line of high-kicking girls and red nosed comics and his most successful shows were straight plays.”

Given the brutality of the war in Asia, Hawkins was, on the whole, wonderfully lucky. He endured no fighting, bombing, rationing or drills. In fact, he even found himself a new girlfriend: the beautiful, blonde, English actress Doreen Lawrence, the two would later marry.

The only downside to ENSA was wading through endless complaints from ‘turns’ about threadbare living conditions, the discomforts of heat, cold, fleabag hotels, inoculations, rats, malaria, dengue, blackwater fever, dysentery, parasites and bedbugs.

In 1945, with the war in Europe winding down, Jack confessed he did not feel right about saying ‘Thanks boys, and goodbye’—especially with so many troops still spread across Asia—so he remained at his post.

Though he became a virtuoso in all departments of military entertainment, he championed good theatrical productions. When John Gielgud arrived in India to perform Hamlet, he wrote to his superiors in London: “Gielgud was sweeping the Far East. Frills, legs, and variety, so necessary an antidote to battle strain, have given place to a wish for good theatre. A new taste for the theatre has been awakened in the men, and I believe it will live on when they come home.”

For his part, Gielgud observed Jack in uniform clutching his treasured brown leather swagger stick and looking “very much the sort of head boy. I think he rather enjoyed the authority.”

In the end, India was an exhausting but wholly unique experience, but Jack was glad to leave.

“He emerged from the war a different man,” Picturegoer later noted. “He took on a different personality. Maturity had caught up with him. He had broadened mentally and physically. His shoulders were wider, his whole build heavier. His face had gained character lines.”

After demob, as the war faded into the far corners of his memory, Jack responded to the call of duty on the silver screen by creating the image of a dependable English hero.

With his barrel-chest and raspy voice, he was soon considered the living embodiment of British ruggedness, resilience, straightness, and compassion.

For the next 20 years, a spectacular pageant of epics saw him fighting Germans, Italians, Japanese, U-boats and the Luftwaffe, all from the safety of Pinewood Studios.

In fact, someone once said, if Jack Hawkins had made a serious attempt to play a criminal or Nazi, he would have been booed offstage.

Jack Hawkins: A Biography by Nathan Morley is published by Fonthill Media.